James Bagnall

I caught up Saturday morning with Chris Scott, the realtor who for the past 16 years has been selling homes under the Keller Williams Integrity Realty banner. He had just finished showing homes for a military official who was being transferred from New Brunswick to Ottawa.

“When he returns to New Brunswick, he’ll have to self-quarantine for two weeks,” Scott said. “He’s got to find something this week or he’ll have to do it all over again.”

Bagnall: Why Ottawa house prices are rising even as employment numbers fall

That is just one example of what’s driving up Ottawa house prices in the midst of a pandemic. Scott, who specializes in real estate services for military personnel, pointed out that many potential buyers have been frustrated by the scarcity of listings and the resulting bidding wars.

A recent listing in Munster Hamlet, for instance, attracted eight offers, pushing the $415,000 asking price for the single-family dwelling to $460,000.

“The buyers are there,” Scott said. “They’re ready.”

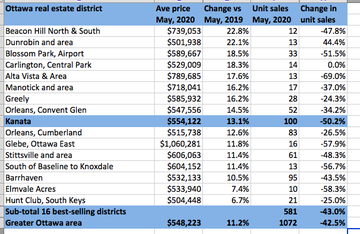

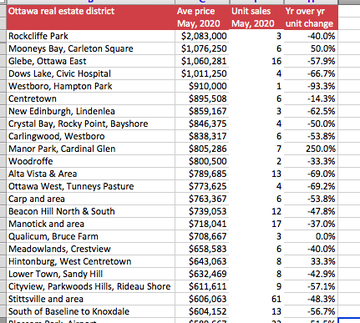

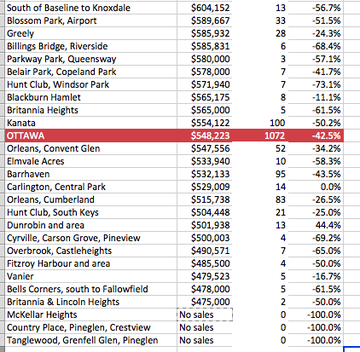

This, in part, explains why average prices for resale homes in May jumped 11.2 per cent year over year to $548,000, while sellers of condos saw average prices surge 15.5 per cent to nearly $344,000.

What’s missing, big time, is available properties. At the end of May, just 1,933 residences and condos were listed for sale in Ottawa, down 50 per cent from a year earlier. This, in a city with 264,000 owned properties, including 59,000 condos.

Clearly some of the scarcity reflects potential sellers’ concerns about COVID-19. But in the past few weeks, Scott said, people who had delayed putting their houses up for sale are now calling him. “They’re more comfortable with the safety features we’ve put in place as an industry,” he noted, “as well as with the favourable trend in the number of infections.”

Yet the underlying weakness in the local job market is profound. The capital region’s jobless rate soared from less than five per cent pre-pandemic to more than 14 per cent in May.

That’s more than 100,000 people out of work in a regional workforce of 757,000. And that doesn’t include the many thousands who have been laid off temporarily as a result of COVID-19, but aren’t counted among the officially unemployed. Many have little idea when they’ll be called back to work by employers.

So why aren’t the jobless numbers having a bigger impact on house prices?

Part of it has to do with just who is being laid off. The hardest hit have been young and lower paid workers, people unlikely to be involved in bidding wars for half-million-dollar properties.

During the year ended in May, nearly one-third of the net 2.6 million jobs shed across Canada were those of people aged 15 to 24. This cohort accounts for just 14 per cent of the total working-age population. Drilling a little deeper, one million of the lost jobs were part-time; fully half of these had been occupied by young workers.

The year-over-year decline in jobs was sharpest in restaurants and hotels (down 45 per cent), culture and recreation (off 25 per cent) and wholesale and retailing (down 16 per cent).

In the national capital region, these sectors combined to account for roughly two-thirds of the jobs lost since May 2019.

These sectors have been sustained by a small army of service workers, many now relying on government cheques until the post-COVID-19 recovery, whenever that comes.

On the other hand, the Ottawa region is buttressed by several sectors that appear to offer rock-solid employment prospects: public administration, health, education and high-tech. Together, these make up about half the total workforce in Ottawa and Gatineau. Remarkably, their employment levels are roughly the same as a year ago.

“A lot of people have a direct connection to a government job here,” Scott said. “Even if they’re not employed directly, often they have a spouse or relative who is.”

That kind of security can make a profound difference when signing up for a 20-year mortgage.

Core pillars of Ottawa’s high-tech industry are also spinning off well-paid jobs, not to mention sharply higher share prices that benefit employees. Many of these firms are supplying technologies in high demand in the era of COVID-19. Shopify helps retailers build or expand online businesses. Ciena, Ericsson and Nokia all build the underlying infrastructure that enables communications networks in a work-from-home world. Software built by Kinaxis makes sure some of the globe’s largest corporations can track and re-orient their supply chains as closed borders force such readjustments.

Provided the globe doesn’t slip into an extended economic recession, these jobs and paycheques should be safe enough to help underpin Ottawa’s resilient housing sector.

The real danger for the market would be political. If the federal government later decides to trim the public service as it begins the long job of reducing the country’s suddenly massive spending deficit, the price of houses locally would — on past experience — weaken quickly. For the moment, that scenario appears a long way off.

Huge yr over yr drop in volume of residential resales in most Ottawa real estate districts in May according to #OREB1. Yet ave prices are up 11.2% to $548,200 across city. Attached: top 16 districts by units sold + top 50 by price. Yes, the impact of the virus has been profound.

14Twitter Ads info and privacySee James Bagnall’s other Tweets